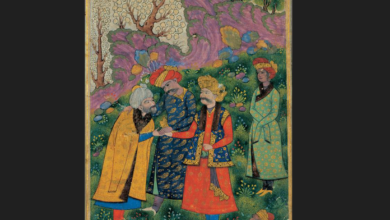

A confluence of spirits: Aurobindo & Rabindranath

In these two seer-poets we see not merely a shared past but a shared destiny

Is there a common spiritual and intellectual thread between two of India’s most luminous sons — Sri Aurobindo and Rabindranath Tagore? The answer is a resounding yes.

Is there a common spiritual and intellectual thread between two of India’s most luminous sons — Sri Aurobindo and Rabindranath Tagore? The answer is a resounding yes.

Both were multifaceted visionaries: Aurobindo — a philosopher, spiritualist, yogi, revolutionary, and poet; and Tagore – a literary genius, reformer, educationist, and the first Asian Nobel Laureate. They were aware of each other’s luminous presence, intellect, and ideals, and deeply respected each other’s contribution to the soul of India.

Sri Aurobindo remains one of the finest architects of India’s freedom struggle and a profound voice of Indian spiritual philosophy after Adi Shankara.

A Mahayogi, a seer-poet and the author of India’s spiritual resurgence, laid down the principles of Integral Yoga – a path toward transforming human life into a divine life. Always alert to such greatness, Tagore held Aurobindo in high regard – just as Aurobindo recognised the ethereal beauty and spirit in Tagore’s poetry.

When viewed today through the lens of history, Aurobindo stands as the prophet of the Eternal Day, the herald of a divine future for humankind, while Tagore, the poet of the dawn, emerges as a guardian of purity and purpose – together, they epitomise the soul of India, eternal and incredible.

Born in 1872, Aurobindo was eleven years younger than Tagore (born in 1861). Their first recorded meeting was at Jorasanko, Tagore’s ancestral home in erstwhile Calcutta, in 1906.

Aurobindo, recently returned from Baroda, accepted Tagore’s invitation to dinner – an event that also featured luminaries like Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose and a visiting Japanese artist. However, their acquaintance likely preceded this, as Aurobindo had been visiting Calcutta occasionally since 1893, orchestrating revolutionary efforts and creating intellectual waves through his bold writings in Indu Prakash, under the series New Lamps for Old.

His radical thoughts shook the political orthodoxies of the time, drawing admiration from fellow thinkers like Tagore.

Tagore’s admiration deepened when Aurobindo became editor of Bande Mataram, the journal that electrified nationalist sentiment across India. So profound was its influence that Tagore wrote to his son, Rathindranath (then studying in the USA), saying that he would no longer send The Statesman, but Bande Mataram, as it carried the soul of the nation.

Aurobindo, then Principal of the newly founded National College under the National Council of Education and Professor of History, shared the same institutional space with Tagore, who was appointed Professor of Bengali. This proximity led to a natural and mutual deepening of respect and interaction.

A memorable moment in their camaraderie came in September 1907 when Apurba Bose, the printer of Bande Mataram, was sentenced to prison. Aurobindo was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Tagore, arriving to congratulate Aurobindo, teased in Bengali, “What! You have deceived us!” Aurobindo replied in English, “Not for long, will you have to wait.”

Nalini Kanta Gupta, Aurobindo’s close disciple, eloquently captured the spiritual kinship between the two: “Both were poets – nay, seer-poets. Tagore, the poet of the dawn; Aurobindo, the prophet of the Eternal Day.”

Deeply rooted in India’s ancient heritage, both envisioned a resplendent future for their motherland. Each believed that India’s freedom was essential to her spiritual and civilisational resurgence. Their works ignited a psychological revolution during the Swadeshi movement and beyond.

Though both eventually stepped back from active politics, they remained deeply committed to their respective missions – Tagore through Santiniketan, and Aurobindo through the spiritual path of Integral Yoga at Pondicherry.

As Santiniketan blossomed under Tagore’s poetic and educational vision, so did the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, shaped by Aurobindo’s yogic insight and the Mother’s dynamic guidance. So deeply moved was Tagore by Aurobindo’s writings and fearless spirit that he paid a heartfelt tribute in person, reading aloud his ode to Aurobindo:

Rabindranath, O Aurobindo, bows to thee!

O friend, my country’s friend, O voice incarnate, free,

Of India’s soul!

Aurobindo, in turn, offered high praise for Tagore’s literary brilliance: “His work is a constant music of the overpassing of the borders, a chant-filled realm in which the subtle sounds and lights of the truth of the spirit give new meanings to the finer subtleties of life.”

On a specific poem of Tagore, Aurobindo once wrote:

“But the poignant sweetness, passion and spiritual depth and mystery of a poem like this, the haunting cadences subtle with a subtlety which is not of technique but of the soul and the honey-laden felicity of the expression, there are the essential Rabindranath and cannot be imitated because they are things of the spirit and one must have the same sweetness and depth of soul before one can hope to catch any of these desirable qualities.”

Aurobindo also admired Tagore’s unique ability to rejuvenate the soul of Bengal’s devotional poetry: “One of the most remarkable peculiarities of Rabindra Babu’s genius is the happiness and originality with which he has absorbed the whole spirit of Vaishnava poetry and turned it into something essentially the same and yet new and modern. He has given the old sweet spirit of emotional and passionate religion an expression of more delicate and complex richness voice-full of subtler and more penetratingly spiritual shades of feeling than the deep-hearted but simple early age of Bengal could know.”

Their lives converged powerfully during the national upheaval following the 1905 partition of Bengal. Both were pivotal in awakening national consciousness, riding the crest of India’s first wave of nationalist resurgence. Tagore likened the First World War to a “Yuga-Sandhi,” a turning point between the death of the old world and the birth of a new, albeit through a dawn of suffering. Aurobindo echoed this vision, viewing the war as a cataclysm engineered by Nature to shatter the decaying order and hasten a new age.

In these two seer-poets — one rooted in spiritual activism, the other in creative humanism — we see not merely a shared past but a shared destiny. They remain the twin flames of India’s renaissance – the eternal dawn and the eternal day.

Also read: