Cost of freedom: Bangladesh’s political crisis and Mujib’s legacy

Political decisions of Mujib after liberation had an insidious impact that exacerbated antagonism in the country

A students’ protest against the Sheikh Hasina government’s policies, particularly a quota system to allocate civil service jobs, turned violent, leading to a major political crisis in Bangladesh last year. Hasina’s government was finally toppled on August 5, 2024, and she was forced to flee the country. However, it did not put an end to the violence, which, by then, had turned into a show of fanaticism targeted at the religious minority of the country.

A students’ protest against the Sheikh Hasina government’s policies, particularly a quota system to allocate civil service jobs, turned violent, leading to a major political crisis in Bangladesh last year. Hasina’s government was finally toppled on August 5, 2024, and she was forced to flee the country. However, it did not put an end to the violence, which, by then, had turned into a show of fanaticism targeted at the religious minority of the country.

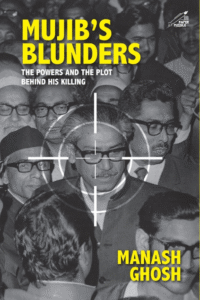

The upheaval that marked Bangladesh’s worst political crisis after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibar Rahman half a century ago cannot be seen as a standalone event without considering its roots in history. The political decisions of Mujib after liberation had an insidious impact that exacerbated antagonism in the country. A recent book, the second in the Bangladesh series, by renowned journalist Manash Ghosh, takes a close look at the historical blunders committed by none other than Bangabandhu.

Mujib’s Blunders: The Power and The Plot Behind His Killing, published by Niyogi Books, documents the time and history of events that led to the bloodbath in Bangladesh in 1975 (August 15, 2025, marked the 50th anniversary of Mujib’s killing) and eroded the secular fabric that Mujib had dreamt of during the Liberation War.

Friends & foes: Mujib’s disillusionment

When Bangladesh won the Liberation War with India’s military support, Sheikh Mujib was still in a Pakistani prison. In his absence, Tajuddin Ahmed, once his close confidante, took up the mammoth task of nurturing the newborn nation. His government-in-exile was functioning from erstwhile Calcutta, arduously and efficiently stitching together an administrative structure and focusing on building an economy from scratch.

However, nefarious elements within the Awami League, along with pro-Pakistan leaders in the country, had already started their secret campaign to malign Ahmed and destabilise the new government. The ruse that they created about Ahmed’s close inclination towards India and his purported role as the neighbouring country’s stooge clouded Mujib’s vision and his ability to think independently.

The vile anti-Tajuddin campaign had its manifestation in Mujib’s altered behaviour and changed allegiance towards those who would later become his and his government’s nemesis. The ignominy that Tajuddin had to face owing to Mujib’s various political and administrative decisions over the months following his return to Bangladesh left the former leader disenchanted.

The image of India, which played a crucial role in the Liberation War, was also vilified. From blaming India for supplying fake currency, accusing its railway officials of stealing machinery, to disparaging its role as an arm-twisting big brother, the anti-Mujib coterie tried every trick to unnerve the already agitated population of the new nation.

Mujib was overwhelmed by this cornucopia of falseness, and instead of controlling these rogue elements, he allowed them to flourish in his government.

Fading secularism

The mind game began when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto visited Mujib in his cell before his release. “It was Bhutto who was first to sow the seeds of deep mistrust and hatred in Mujib towards Tajuddin by telling him that Tajuddin was a clear winner in the power game that had now gripped Bangladesh,” Ghosh wrote.

Later, Tajuddin had to unceremoniously hand over the responsibilities of Bangladesh to Mujib at the latter’s direction. The Bangabandhu never cared to ask his once close aide what adversities he had to undergo during his absence.

What seemed more menacing, especially for posterity, was Bangabandhu’s gradual deviation from strong secular beliefs and the vision to set up a secular nation. This was first noticed in his speech after he returned to Bangladesh. His emphasis on Bangladesh’s Muslim identity surprised many seasoned journalists and political observers of the time.

Months later, his decision to set up a government-aided Islamic foundation to propagate Islamic philosophy was seen by secular intellectuals of the country as “an extreme retrograde step with serious political and social ramifications”. Over the years, the country witnessed the monstrosity of religious fanaticism that brought back the horrors of the past for the minority section.

Narration of history

Ghosh was a young journalist with The Statesman, the Indian English daily, when he reported on the Liberation War. His first book, Bangladesh War: Report From Ground Zero, was an account of the atrocities of the Pakistani army in East Pakistan and the resilience of the young mukti joddhas.

In the new book, he continues this narration through an important time in the country’s history. As the then Dacca correspondent of the newspaper, he gives first-hand experiences of the events that led to the assassination of Mujib and 18 of his family members, followed by the killing of top Awami leaders in prison. He also gives an insight into India’s diplomatic relations with its newly formed neighbour, which would help readers understand the current bilateral ties with Bangladesh.

The Epilogue provides a synopsis of the current crisis in the country, the US role in the destabilisation of the political situation and Sheikh Hasina’s timely escape from the same fate as her father. The US role, in particular, both in the past and in the present, is an important anecdote in the context of the current global politico-economic developments and key business ties between India and Bangladesh.

The new book is a necessary sequel to the first edition, without which the narration of Bangladesh’s struggle and liberation would have remained incomplete. For those interested in the history of Bangladesh and Indo-Bangla relations, the two books will be great reference points.

Book: Mujib’s Blunders: The Power and The Plot Behind His Killing; Author: Manash Ghosh; Publisher: Niyogi Books; Pages: 475; Price: Rs 795

Banner image: This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.