BOOK REVIEW: Better late than never collection of late-blooming Indian haikus

One of the most difficult jobs in this world is to define poetry. One of my enduring memories of institutional reading of literature is a professor asking our class “What is poetry”, taking 15-20 answers and then declaring “All of you are partially right and partially wrong”. Because, he explained, poetry is like one’s own mother. One can say a thousand things if he/she is asked to describe her. Yet something shall remain left out. Naturally, it is not easy to define a sub-genre of poetry, especially if it is an imported form.

One of the most difficult jobs in this world is to define poetry. One of my enduring memories of institutional reading of literature is a professor asking our class “What is poetry”, taking 15-20 answers and then declaring “All of you are partially right and partially wrong”. Because, he explained, poetry is like one’s own mother. One can say a thousand things if he/she is asked to describe her. Yet something shall remain left out. Naturally, it is not easy to define a sub-genre of poetry, especially if it is an imported form.

However, Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih, one of the editors of Late-Blooming Cherries, has made a painstaking effort in his note to give the reader a rough idea about what haiku poetry is. It could be irrelevant to someone with academic involvement with poetry but is particularly useful for a general reader like me. As he quotes British critic Chris Baldick to say haiku ‘is a form of Japanese lyric verse that encapsulates a single impression of a natural object or scene, within a particular season’, I begin to think this is not as foreign as I thought. Learning about the connection of haiku to Zen Buddhism brings it closer to my Indian sensibility. This is the country of ‘doha’ (couplets containing spiritual truth) after all. However, hardly any haiku contained in this collection is spiritual. Then again, the form most poets have adopted – two lines building up to a crescendo – reminds me of Urdu ghazals which consist of multiple ‘sher’ that are complete in themselves, having a clinching last line.

Once the editors have peeled off the foreignness of these haikus, the poetry not only reads familiar but starts to inspire the emotions it means to. It is said that poetry resides between the lines. The greater the poet, the more he says through the unwritten words. It seems that job is all the more important in haiku because Kynpham Sing’s note explains, haiku’s “suggestive quality is chiefly owing to the presence of imagery, which the haiku cannot do without.” Therefore, in this form, the poet has to draw as powerful an image as he can with as few words as possible. The poets in this collection have excelled in doing that. There are beautiful images to be found as well as haunting ones, like the following by Arvinder Kaur:

Courtroom

How white the shirt

of the rapist

……………………………………..

or by Anju Kishore:

Bombed homes –

talks go round and round

the table

……………………………………………

These are images drawn with words that stay with you. Reading a woman writing the first three lines is a highly Indian experience today. At the same time, the universality is unmistakable. Anju’s lines bring to mind the scenes beamed to our mobile phones and TV sets from Gaza every moment. This is not forced but spontaneous contemporaneity that touches the universal.

On the other hand, some poets in this collection have written highly personal lines that talk to the reader individually. Priya Narayanan, for example, writes:

Empty sky –

how heavy this jar

filled with your ashes.

……………………………………………

Death and loneliness are also running through the veins of editor Rimi Nath’s haikus.

Crowd at a graveyard –

the world is

a burial ground

steam from a kettle:

the soul

leaving the body

………………………………………

The most startling one says:

success –

a lone tree

standing

…………………………………..

Her co-editor Kynpham Sing is more outgoing and seems to take a lighter view of the world around him.

Stupas of Sanchi –

a monk under a tree, lost

in a mobile phone

………………………………………..

Sometimes his sense of humour turns black

city’s cluttered drains

even unwanted infants

are thrown in

…………………………………..

Kynpham Sing has a way with words which allows him to even express despair with humour

region’s backwardness

Explained by a road sign:

‘slow men at work’

………………………………………..

But like a true poet, nature’s beauty does not escape him despite all this. He has been able to conserve the wonder of a child inside himself:

Creepy caterpillar,

when did you become

these flying colours?

……………………………………….

The same quality can be found in Vandana Parashar, who writes:

unexpected showers

every puddle sets free

the child in me

……………………………………….

This despite death and other troubles dotting her writing

peace memorial

I walk a mile

in father’s shoes

…………………………………….

how many more

clouds will pass before it rains

-miscarriage

……………………………………..

Troubles of the real world perhaps find the best expression in the words of Brijesh Raj:

fissured fields

watering the crop

with his tears

………………………………………

family reunion

the widest smile

the counsellor’s

………………………………………..

And in A Thiagarajan’s haiku:

new actors –

Gandhi is shot

again

Kala Ramesh has taken the experiment with the form a step farther and written one-liners like: did Ganga dream of being the city’s sewage?

But if it comes to pouring one’s bleeding heart out, Teji Sethi is the best of the lot. See for yourself:

gunshots

I know nothing

of lullabies

………………………………………

as it goes

with the wind, this cherry petal

so shall I

…………………………………

his last trip

on the waters of the Ganges

a floating urn

………………………………..

amavasya

my scars eclipsed

for a night

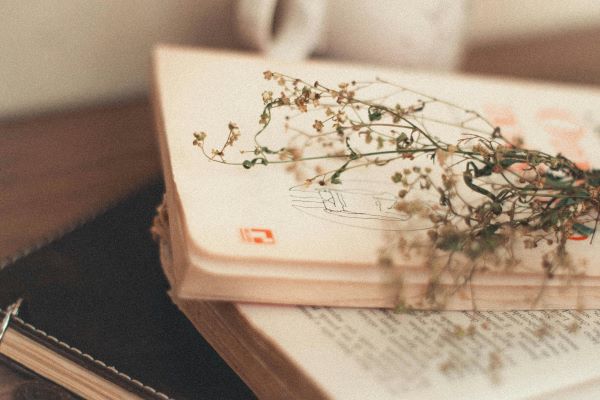

The success of this collection is in bringing all the nine tastes – nava rasa, as they are called in Indian aesthetics – together in this beautifully illustrated collection of haiku poetry. Mugdha’s cover gives it the look it deserves.

Book: Late-Blooming Cherries: Haiku poetry from India; Edited by: Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih and Rimi Nath; Publisher: Harper Collins; Price: Rs. 399