‘A scenographer should not be confined to any particular belief system’

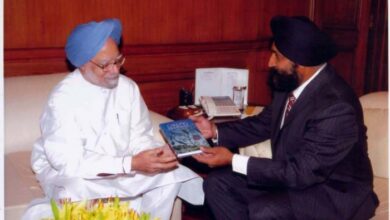

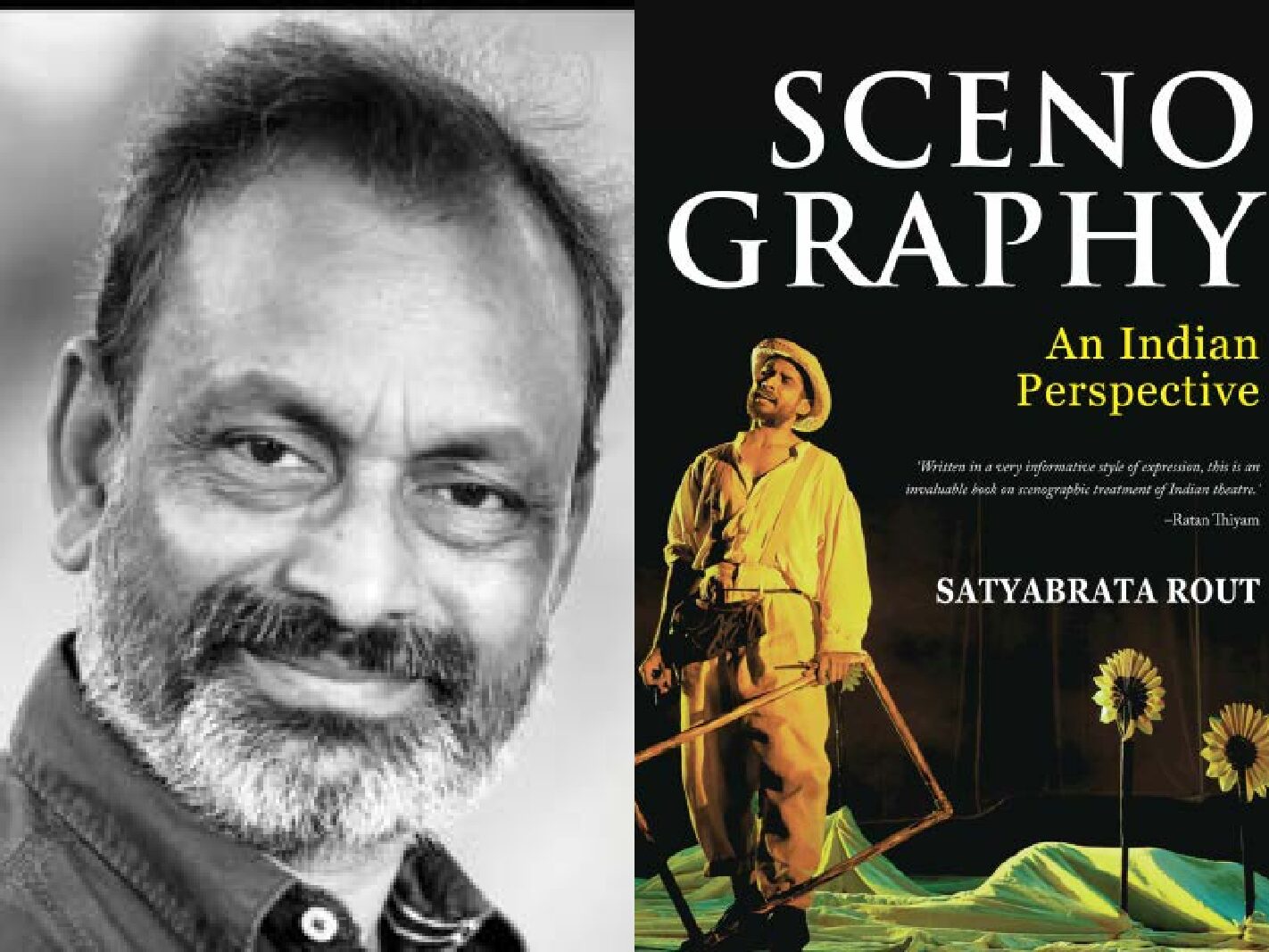

Noted scenographer & director of contemporary Indian theatre Dr Satyabrata Rout talks about his new book, Indian theatre & his journey on stage

How did you get interested in theatre? Can you please describe your journey on stage?

I woke up to an atmosphere of music, theatre and literature at my home and in the nearby vicinity. I was born in Odisha, where the ritualistic and spiritual mindset of the people is their way of life. I grew up with the sound of kirtan, mridangam, jhanj, ghungroo, khool, khanjani and with various native sounds, songs and dance during festivals and ceremonies. From the beginning, I was exposed to Odia literature, folklores, traditional art forms and folk theatres such as Pala, Daskathia, gotipua dance, etc. My forefather used to run a Jatra company during the British Raj and travelled the state with the entire paraphernalia of the performance, to present their shows at different occasions and festivals around the state. Being a child, I have seen my grandfather playing violin and bagpiper which were the primary musical instruments of Jatra. My father was a principal in a government school who used to direct and act in plays during the school annual functions and in other occasions. I am sure, this childhood literal and cultural environment were deeply rooted in me and developed a discipline that brought me to theatre. The natural surroundings of Odisha had a great impact on my visual sensibility. Landscapes and low-lying hills, rivers and sea, flood and cyclone, festivals and rituals, etc. became instrumental for my visual sensibility.

Gradually, I got involved in the village drama during the festivals. We would collect alms from the village folks to sell them to raise money for the drama. This was the most exciting moment of my life. During my college time, I joined in the dramatic society and participated in the college dramas regularly for four conjugative years. We performed plays of Arthur Miller, Jean Paul Sartre, Bernard Shaw, Shakespeare with the plays of many Indian playwrights such as, Mohan Rakesh, Madhu Ray, Manoranjan Das, Badal Sircar, etc. I was fascinated by the ‘Chhau dance’ and started learning from an exponent guru while in the college. Painting was my passion from the childhood.

I came in contact with Mr BV Karanth, a legendary artist and the then director of the National School of Drama in 1979, while I was involved in group theatre activities at Bhubaneswar. A meeting with Karanth paved the way for my career in theatre. I got admitted in the National School of Drama in 1980 through a rigorous selection process. I wanted to become an actor in the drama school but I could not participate in the plays due to my poor accent in Hindi language; I was given only minor roles. Within a few months in the drama school, I decided to shift my career from acting to design and direction. My visual sensibility and reading habits became my foundation for this new profession.

After a long and painstaking work in theatre with many odd and even assignments, freelancing, I joined University of Hyderabad as a professor of scenography in 2007. My practice-based knowledge, global working experiences and teaching involvements, reinforced my academic career and prepared the ground to formulate a unique concept, new to Indian theatre, The Visual Theatre. I started envisioning theatre from this point of view and developed working methods for practicing the components of visual theatre. My recent productions, such as Animal Farm, Ebang Indrajit, Matte Eklavya, Tumhara Vincent, August Ka Khwab, Iphigenia, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakuntala, and Adding Machine, etc. have been designed by following those principles I laid down towards conceptualizing the “Visual Theatre”. My recent book on Scenography is the congregation of those methods and principles, I adopted in the recent years.

What is Scenography?

Theatre from its inception has been developed as an audio-visual medium. The Natyashastra terms it as ‘Drishya-Kavya’, or visual-poetry, which means, ‘a poetry that is visible in a given space’.

Scenography endorses Drishya– visuals, prepares ground for the Kavya- poetry to be visible for its audience and creates scope to experience those visuals. Being an integral component of performance making, scenography precisely brings opportunity to manifest the visuals through the ‘actor-audience-space’ integrations. The actors in collaboration with the ‘stage-space’ formulate a set of symbolic images to be transposed to the viewers’ mind, expanded and realised through subjective interpretations. The audience is free to conceive, imagine, and comprehend those visual symbols by passing through his/her individual journey of life in accordance with text, physical gestures, spatial compositions, sound and music, and through various stage symbols. The responsibility of scenography is to guide the viewers to evoke those experiences with the help of a group of actors who amalgamate and animate the space into a living entity. Thus, scenography orchestrates between actors, space and audience by blurring the distinctive line of ‘creative practices’ (actor’s physical presence, voice, direction, design, text, and viewership) and the ‘technical practices’ (sets, costumes, props, masks, managements, lights, sound, etc.) through a collaborative process.

With actors, it explores these creative and technical practices, and successfully passes the visual experiences to the viewers’ imaginations and initiates the journey along with the dramatic actions. To initiate the audience imagination and guiding them through this journey, scenography explores possibilities through its various components, such as text, space, props, masks, sets, lights, sound, and costumes, etc. Like a piece of sculpture, the three-dimensional stage space is cut into horizontal, diagonal, and vertical planes and sections through the actors’ physical and oral presence to brings out the best possible visuals (real and imaginary), enriched with kinesthetics. Through this process, a narrative is constructed in time and space dimensions — interchangeable, and symbiotic within animate (actors) and inanimate (space and design) elements of the performance, playing with the spectators’ imaginations. Therefore, scenography forms the visual lexicon of the performance. It is the art of visual writings of the stage space that is readable through the eyes like paintings, sculptures and other visual arts in time and space dimensions with difference.

How did the concept of writing this book come to you?

Hardly any documentation available on scenography with an Indian orientation that Indian theatre has been craving for a practical treatise in this regard for quite a long time. Apart from a few interviews or memoirs of productions that pop up in the columns of a newspaper supplement or the pages of a magazine, nothing substantial has yet been brought out. Scenography has been largely redefined in the West by bridging the void between designers and directors in the recent past. But it is a sad truth to acknowledge that such an ideology, which had a profound influence on its immediate world, has not yet been remodelled and chiselled to suit the Indian scenario. Despite having a considerable number of creative theatre makers and scenographers with international acclamation, Indian theatre lacks proper documentation of the works of our masters. With all the resources, we have failed miserably, beyond words, to theorise our practices till date. It is at this juncture that the idea of conceiving a book on this perspective germinated in my mind to showcases its uniqueness. Among the many things this book pioneers, the most prominent is the analytical visual descriptions of the masterpieces of Indian play productions.

Going back to the early 80s, the term ‘Scenography’ was very much missing from the academic scene that left us with nothing other than ‘Scenic design’ to perch on. Ironically, these terms carry different connotations. While the former deals with the entire space and its visual vocabulary inclusive of the actors and the audience, the latter emphasises on the spatial arrangements of the play and more related to its technical aspects.

However, they complement each other and upon reaching a certain juncture, they intermingle to form a single entity. But lack of proper resource materials kept us ignorant about the current trends of world scenography. The available materials in those days were based on western practices with references from western productions and plays. To understand them, it becomes mandatory to be aware of those productions. The longing for a book that reviews the themes from an Indian perspective as turned out to be an overwhelming urge in me. Perhaps it is this impetus that provided momentum for bringing out this research document. I was always dreaming for a book that talks about our theatres, narrates our productions, depicts the visual imageries that emerged out of our traditions and sketches out the forms and colours of Indian cultures and design.

I do not know exactly when and how I stepped into this mesmerising world of theatrical visuals, perhaps the missing link can be traced in my childhood creativity. When I adopted teaching design and direction in various theatre workshops and group theatres after graduating from the National School of Drama in early 80’s, I found most of my students were from the remote corners of India with no background of theatre vocabulary. Most of them were completely ignorant of the western trend of performance design. Western plays remained alien to these peripheral practitioners. At the same time, to formulate a concept out of the popular Indian productions was a difficult task for me. Especially in design, since no reference materials were available related to Indian theatre. So, I started teaching out of my personal working experiences. In the beginning it was arduous to develop a definite tone, but gradually over the period the teaching methodology advanced into systematic order.

Gradually in the process of teaching, I developed passion to conceptualise various methods which I have come across in my profession. I started working on the first draft of this book after I joined in the Department of Theatre at University of Hyderabad in 2007. But soon I realised my experiences and working knowledge are not adequate enough to bring out an outstanding reference book that covers all aspects of theatre arts and design. A break was inevitable to gain more ideas about the theatre history, architecture, art and design, and culture as a whole. The more and more I referred to the available materials on Indian theatre criticism and productions, I revitalised myself to restart this massive work.

What kind of research did you undertake to write this book?

Writing a book on Indian performance design and scenography is not an easy job, since the field is vast with hardly any available reference materials. At this juncture of time, my working experiences and practices served as the primary source of my research. Fortunately, I have a wide range of fieldworks with almost all Indian eminent practitioners, institutions, group theatres and professional repertories of the country. Also, I have acquired an understanding of Indian classical, traditional and folk theatres and observed them from close proximities. My long associations with the most eminent theatre personalities of India such as, Habib Tanvir, Ebrahim Alkazi, BV Karanth, RG Bajaj, Prof. Raj Bisharia, Dr Nissar Allana, Ratan Thiyam, KN Panikar, Prof. Ankur, Prof. Bansi Kaul, Prof. Robin Das, Dr Anuradha Kapoor, Dr Neelam Mansingh Chawdhury, etc., helped me a lot to analyse and assimilate there practicing methods on scenography and performance design in to this book. Moreover, interviewing these personalities repeatedly, opened many undiscovered chapters that were conceptualised in my writings. In fact, some of those interviews are kept in their original forms in this book to make the readers aware of their process. I had to plunder libraries and research centres such as, National School of Drama library, Indira Gandhi Centre for Arts, Natarang Pratisthan, Natya Shodh Sansthan, etc. to identify materials related to my research. I have collected many archival materials and production photographs, brochures, etc., from various repertories and group theatres for this book. My research included in finding written resources of this subject from various journals and magazine, such as, The Rang-prasang, Natarang, Theatre India, The Seagull quarterly, etc. I had gathered related paper reviews of various reputed Indian productions either through personal relations or through internet for this purpose.

An important aspect of this book is the study of Indian ancient theatres, various performance spaces, folk and traditional performances, in which I have extensively covered their scenographic atmosphere. Repeated visit to these sites, ruins and caves, watching various traditional, folk and popular theatres, travelling across the country and analysing their performance design and technics, and finally assimilating all these materials into writings through a scenographic vision, took more than 12 years for its completion. These years taught me to focus on the subject with a good deal of patience. More than writing a book, it is the knowledge and information that I received over these years, I cherish.

I hope this book will be helpful for the readers to acquire first-hand information about many interesting aspects of Indian theatre making and performance design. Indeed, this book will be a good reference to the practitioners, scholars and students and certainly will orient the young minds for scenography across the globe and to make them understand the performance traditions of India and Orient.

How can scenographers contribute to the world of theatre in India? At what point during the course of the play do they pitch in?

Unfortunately, Indian theatre has not yet completely awakened to such an interesting creative art form. The general practices across the country are yet to assimilate scenography into their productions. Out of a few Indian scenographers and designers, who have acquired in-depth study of the subject are mainly directors who use to conceive their own performance design. In most of the practices, scenography remained untouched by labelling it as costly affairs. Therefore, the potential of scenography is not yet been fully explored in Indian theatre, but gradually gaining momentum in the recent years.

Keeping aside its technical aspects, scenography is emerging as a concept in most of the academic productions in India, whose influence is clearly visible in contemporary practices in the 21st century productions. Exploration of various kinds of performance spaces, creating scope for audience and actor integrations, emphasising on visual aesthetics, developing awareness for design and visual interpretations are some of the areas which are gradually being adopted into contemporary Indian theatres. This becomes possible due to the practicing methods adopted by our Indian scenographers.

Scenography, being an applied form of visual art needs constant interactions with the dramatic text from the beginning of the process. It grows day by day with the production through actor-space integration, merging into the style of presentation. Therefore, it is essential to involve scenography from the beginning of the process. Indian theatre is yet to create adequate space to incorporate this creative art form in to its performance design.

Also, how does scenography work in the already established traditional theatre like Yakshagaana or Kathakali and/or in the street theatre formats?

Our Indian traditional theatres use empty space for their presentations. In that performance space, a virtual dramatic space is fabricated out of actor’s imaginations. Through abstract gestures and gaits the actor creates an environment of indicative spaces in audience mind, in which the viewers visualise the environment in his/her psyche. For example, in Kutiyaattam performance, during a combat fight between Bhim and Ghatotkatch, the audience visualise the scene with all its ambiences, including mountains, forests, trees, etc. along with the physical power of these two meta-physical characters, in spite of an empty performance space and miming gestures of the actors. With the actor and space integration, this becomes possible and that is the strength of Indian scenography. Often scenography is created out of improvisations and symbolic use of props and costumes in traditional theatres. One must have observed, how a hand prop is symbolically transformed and explored in the dramatic context being a part of the performance in our classical and traditional theatres.

In Pandavani (folk theatre of Chhattisgarh region) performance the singer actor explores the visual aesthetics of a Tambura (a musical instrument), a hand prop in various means to narrate the story. Similarly, the entry of actors behind the Yavnika (half curtain) explores and expands the possibilities of scenic grandeurs in Indian classical theatre.

But the things become different in any street or environmental performances. These performances usually adopt and improvise the space. In this case, the existing space is adopted and transformed into dramatic spaces through actors’ interactions with the space and creates a sense of belief in the audience mind.

In a sense, a person in charge of scenography has to be in touch with the local cultural ethos. How can this be achieved in a country like India where an auspicious cultural symbol in a particular geography or culture could be considered ominous in another?

It is true that a scenographer has to align with various cultural ethos of the country. But he/she should not be confined to any particular belief system. Indian cultural ethnicity always remains diverse that gives rise to various cultures and believes which is clearly marked in our rituals and community activities. The ambience of colours, patterns and forms of our cultural ethos are diverse and of course that is the strength of Indian arts and cultures. Being a scenographer, our responsibility is to adopt socio-cultural aesthetics and reinterpret those narratives into visual metaphors in the performance. But one must not stick to any specific culture, idea and ethos, rather work in accordance with the demand of the productions without any prejudice.

How does a scenographer work in a world that is filled with easily accessible mediums such as digital banners and electronic backdrops?

Of course, it is challenging, but working in both the media remain exciting for a scenographer. Both the medium- ‘digital’ and ‘live’, have their possibilities and limitations which a scenographer must understand prior to working in these mediums. While live medium will always remain three-dimensional and interactive, digital medium is two-dimensional with one way communication. This has to be taken into consideration while designing a production.

Today’s world is more accessible to digital and electronic mediums. One can get everything without going out from his house; everything is served over the table, easily. But the purpose of scenography is different. It is not to provide any spectacular visuals in front of your eyes and make you a passive observer, it creates an experience of being within that atmosphere and happenings. It arouses among the audience the stimuli of being an active participant of the event through human imaginations, which an electronic medium may not provide. Moreover, The actor-audience communion in a given space and their interactions solves many social issues that a digital or electronic medium cannot resolve. That is why theatre being a visual medium is universal that lives and talks in the present time

What are your thoughts about reusing and recycling props and the role of a scenographer in managing waste?

Nothing goes waste in theatre. Every bit of the elements brings new meaning and add to the interpretation of the play. The creative endeavour of scenography, each time reinterprets objects, props, sets and costumes, etc. with new contexts. Moreover, contemporary Indian theatre used to exist within financial constrain, for which we are habituated to reuse and recycling the elements of previous productions. Indian scenographers are more exposed to improvisations for which they explore things with much meaningful way.

What next? Can there really be a formal curriculum for a subject like scenography without compromising improvisations and creativity?

Scenography is an applied form of art having a direct link with its parental form- ‘visual arts’. For a scenographer its mandatory to acquire in-depth understanding of painting, sculpture, architecture and other visual mediums. Also, without a skilled background of theatre practice, this can not be achieved, which means a scenographer needs to be expertise in both the art forms. That is why we have a few scenographers in the world.

Scenography as a formal subject of specialization has already been introduced in the curriculum in some of the Indian Universities and institutions, such as, University of Hyderabad and the National School of Drama, etc. But unfortunately, the course often face many compromising situations due to the lack of trained teachers of scenography in India. Being a teacher of scenography at the University of Hyderabad, I always felt the scarcity of reference materials and books on Theatre design and scenography in Indian context. The recently published book “Scenography: An Indian Perspective” is the outcome of my continuous search for relevant Indian performance design. Hopefully, this book will inspire young minds to adopt scenography as a prospective career and institutions to introduce Scenography as a major focus of study.

~ Team Sunday Monitor